Confused by the difference between redistribution and reapportionment? Wondering what a gerrymander looks like? This is your key to the language and concepts behind redistricting.

Census

The United States Census is a population enumeration conducted every 10 years, the results of which are used to allocate Congressional seats, electoral votes and government program funding. As part of the Census, detailed demographic information is collected and aggregated to a number of geographical levels. This data is used during the redistricting process, both by partisan interests and by redistricting authorities and the courts. The next census day is April 1, 2020. The Census Bureau must deliver population data to the President for apportionment by December 2020 and must deliver redistricting data to the states by March 2021.

Community of Interest

Although the preservation of “communities of interest” is required by many redistricting laws, the meaning of the term varies from place to place, if it is defined at all. The term can be taken to mean anything from ethnic groups to those with shared economic interests to users of common infrastructure to those in the same media market. As it relates to redistricting, it is usually considered a group with shared social, cultural, racial, ethnic or economic interests who may be the subject of legislation. The Brennan Center for Justice provides a helpful summary of some of these uses.

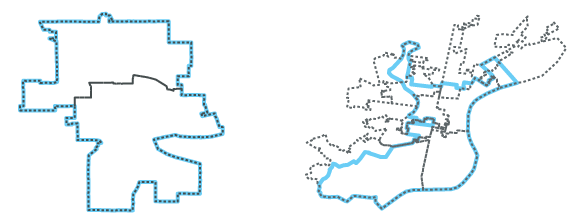

Contiguity

Like compactness, contiguity is considered one of the “traditional” redistricting principles. Most redistricting statutes mandate that districts be contiguous– that is, they are a single, unbroken shape. Two areas touching at their corners are typically not considered contiguous. An obvious exception would be the inclusion of islands in a coastal district.

Compactness

One of the “traditional” redistricting principles, low compactness is considered to be a sign of potential gerrymandering by courts, state law and the academic literature. More often than not, though, compactness is ill-defined by the “I know it when I see it” standard. Geographers, mathematicians and political scientists have devised countless measures of compactness, each representing a different conception, and some of these have found their way into law. For a more in-depth discussion of the role of compactness in the redistricting process, see Azavea’s whitepapers on the topic. The Metric Geometry and Gerrymandering Group has also done a lot of research around the topic of measuring compactness.

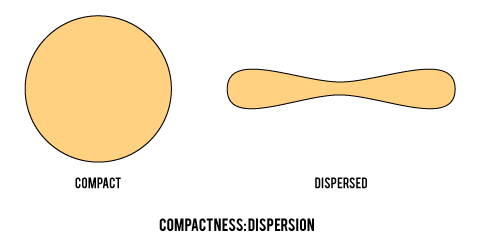

Dispersion

Dispersion-based measures of compactness, such as the Reock and convex hull measures used on this site, evaluate the extent to which a shape’s area is spread out from a central point. A circle is very compact, while a barbell is less compact.

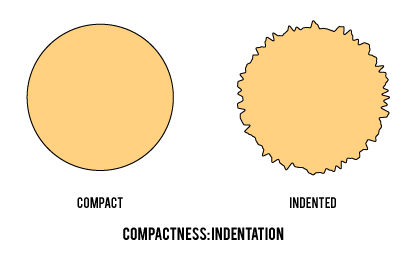

Indentation

Perimeter-area based measures of compactness, like the Polsby-Popper and Schwartzberg measures used on this site, primarily evaluate the indentation of district boundaries. Shapes with a smooth perimeter are more compact, while those with a contorted, squiggly perimeter are less compact.

Gerrymandering

Gerrymandering is the process by which district boundaries are drawn to confer an electoral advantage on one group over another. The term is a portmanteau word formed from the surname of Massachusetts Governor Elbridge Gerry and the salamander shape of the district he approved, which appeared in an 1812 cartoon. Gerrymandering can take on many forms.

Types of Gerrymandering

Political

A political gerrymander is typically conducted by the majority party to strengthen or maintain their electoral advantage. In a 2004 decision in Vieth v. Jubelirer, the Supreme Court rejected a challenge to politically gerrymandered districts due to a lack of justiciable standards; however, the issue continues to become before State and Federal Courts.

Some State Courts have struck down political gerrymandering in recent years, such as Pennsylvania in 2018. However, Federal Courts have been reluctant to rule based on a lack of standards. Recent cases in front of the Supreme Court have challenged political gerrymandering on the grounds of the First Amendment, Equal Protection Clause and Elections Clause of the U.S. Constitution.

Incumbent protection

An incumbent protection gerrymander results from an agreement by both major political parties to draw district boundaries to create safe districts for incumbents. See Fig. 2 in ”Packing and Cracking” illustration.

Racial

Racial gerrymandering is drawing district lines to prevent racial minorities from electing a candidate of their choice.

The term racial gerrymandering initially designated the post-Reconstruction practice which, like poll taxes and literacy tests, was designed to disenfranchise African-Americans. Legislative district boundaries were drawn with the aim of diluting the electoral power of newly registered voters from ethnic minority groups.

Following the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, this practice was prohibited; indeed, in many circumstances, the statute in fact requires the creation of majority-minority districts. The practice of drawing districts that would afford racial and ethnic minorities the opportunity for elected representation has come be known as affirmative gerrymandering or—in a somewhat ironic reversal—racial gerrymandering.

Beyond the requirements of the Voting Rights Act, there are legal limits on drawing districts based on race, particularly for smaller populations. A number of recent Supreme Court rulings—such as Miller v. Johnson, Bush v. Vera and Shaw v. Reno—indicate that in cases where race is the sole or predominant factor, or where the shape of a district cannot be explained on grounds other than race, district boundaries must be held to a strict standard of scrutiny. Absent a compelling government reason for the district’s shape, it will be viewed as violating the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution. In a recent landmark ruling (Cooper v. Harris), the Supreme Court affirmed that racial gerrymandering is indeed still an issue and race cannot be relied on too heavily when redrawing districts.

This is likely to remain a contentious issue, particularly as the demographic composition of the country continues to shift and multiple ethnic minority groups share physical space and merit elected representation.

Prison

The one person, one vote principle is distorted by the inclusion of large prison populations in the calculations of district population, despite the fact that inmates are rarely constituents of the areas where they are incarcerated. In districts that include large, disenfranchised prison populations, the ballots of the remaining voters hold a disproportionate amount of weight.

Nesting

Nesting is a redistricting policy by which the geographical boundaries of two or more state lower legislative chamber districts are completely contained within the boundaries of a state upper legislative chamber district. This can be achieved either by first designating senate district boundaries and then splitting these into house districts, or by drawing house district boundaries and then consolidating these to form senate districts. Nesting is mandated in full or in part in 12 states.

Packing & Cracking

Packing and cracking are common methods of gerrymandering, used to minimize the impact of a voting bloc. Packing concentrates members of a group in a single district, thereby allowing the other party to win the remainder of the districts. Cracking splits a bloc among multiple districts, so as to dilute their impact and to prevent them from constituting a majority. These methods are frequently used in conjunction with each other.

Reapportionment

Reapportionment (referred to as redistribution outside the US) is the process of allocating seats in a legislative body to geographical areas. Reapportionment is particularly important in the case of the U.S. Congress, where the number of seats in the House of Representatives is fixed at 435 and the number of seats allocated to each state is reevaluated following each decennial Census. When the number of seats assigned to a state changes, the state must redistrict.

Redistricting

Redistricting is typically conducted to ensure that district populations are equal in size, thus supporting the principle of “one person, one vote”. For this reason, redistricting typically occurs after a population census, so that district boundaries reflect the most recent, accurate information about population distribution that is available.

Voting age population

When evaluating districting plans, analysts may elect to use the voting age population rather than the total population as the basis of comparison to ensure that the principle of one person, one vote is upheld.

Voting Rights Act

The National Voting Rights Act of 1965 was a landmark piece of civil rights legislation that outlawed discriminatory voting practices– racial gerrymandering among them– that had been used to disenfranchise African Americans. Crucially, Section 5 of the act requires that jurisdictions with a history of discriminatory practices secure federal preclearance for proposed changes to electoral practices, including the introduction of new district plans. Section 2 prohibits any voting practice or procedure that has a discriminatory result, but in 2009 the Supreme Court ruled that this does not constitute a requirement that authorities draw district lines favorable to minorities when they constitute less than half the population.